Last month I kicked off the Everyday Soil Science series with the distinction between soil and dirt. Now that we’re all on the same page and recognize that soil is a “living” resource and not the stuff in your vacuum cleaner bag, it’s time to move on to a discussion of how to “feed” your soil.

Yes, feed your soil.

The idea of feeding your soil doesn’t seem so strange once you become aware of the billions—yes billions—of organisms living in a teaspoon of the stuff. Just like us, those organisms need to eat; and believe me, they’re hungry little buggers. We’ll cover the nitty gritty of what lives in soil in an upcoming discussion; but suffice it to say that soil is alive, and you want to keep it that way. To do so, you need to feed it!

The earthworm. One of the many organisms found in living soil. Photo by: Stephen Andrews

If you’ve attended a Bay-Friendly Landscape or Master Gardener training, in which I have been one of the instructors, you’ve undoubtedly heard me stress the importance of feeding your soil and not your plants. Just think about it for a minute: Long before the magic of fertilizers arrived at a box store near you, plants extracted what they needed from the living soil that they were growing in. I think we can all agree that there were some very impressive plants growing on the planet during the days of the dinosaurs. No fertilizers required. The message here is that if your soil is fit, your plants will be too.

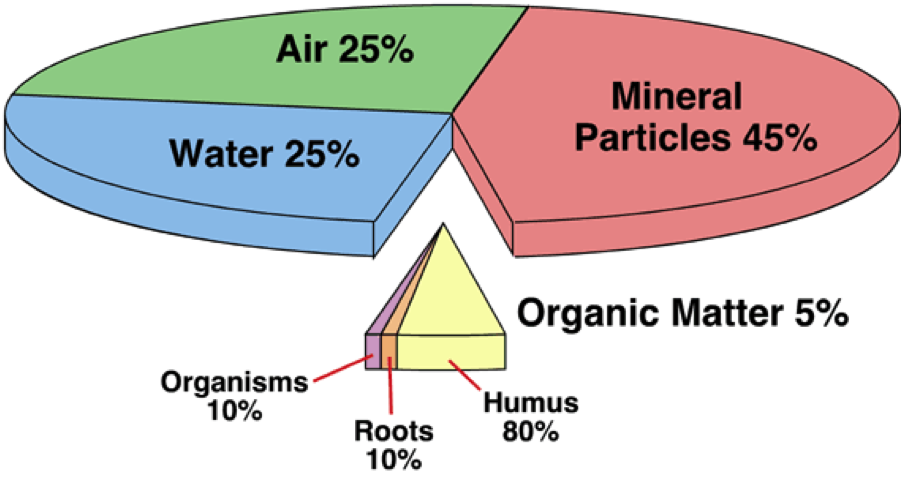

Enter organic matter. Organic matter, specifically decomposed organic matter, is the food that feeds the living biology of the soil. Yet, organic matter—or OM—can be elusive. OM is in big demand. There are lots of mouths to feed in the soil, and they all want a piece of OM (in one form or another). Aside from being in great demand by soil organisms, OM is also a bit diva-like and can be fussy to deal with. It oxides quite easily, and is sensitive to changes in temperature and moisture. In fact, every time we put a shovel, spade, or trowel into soil, we are exposing the organic matter to oxidation.

As you might have noticed, there’s a kind of supply and demand thing going on with soil organic matter. You can think of it as economics meets ecology. In short, our soils are worked so frequently and heavily, that there isn’t much organic matter to be found to meet the demand. In recent years, the U.S. Composting Council started a “Strive for 5” campaign aimed at getting all of us to increase the organic matter content of our garden and landscape soils to five percent. To find out how much organic matter is contained in your soil, you’ll need to collect a representative sample and send it to a certified laboratory for analysis.

Now five percent may not seem like much, but it can be a tall order when we consider that many soils are well below the two percent mark in organic matter content. Now enter you, the gardener or landscaper, who can help feed the starving masses beneath your feet by getting organic matter back into the soil.

How do you add organic matter to soil? Compost, compost, compost!

Making compost from green waste (grass clippings, leaves, branches) and food scraps can boost the organic matter content of soil quickly.

A one percent increase in organic matter can quadruple the water holding capacity of a soil, not to mention keep thriving populations of soil critters happily recycling the nutrients that your plants needs.

I’ll discuss methods of making compost in a future edition of this newsletter.

High quality WM EarthCare™ Homegrown compost is produced from green waste and food scraps.

At the moment, the point is to get organic matter back into your soil, and not in the landfill. Look for sources of compost that are locally produced and are registered with the California Department of Food and Agriculture, Organic Input Materials (CDFA, OIM) program, U.S. Composting Council, Seal of Testing Assurance (USCC, STA) program, or listed by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI). You’ll notice that WM EarthCare™ Homegrown compost is registered with all three of these programs, which are considered to be industry leaders in the development of compost quality criteria.

Consult your Master Gardener office or Bay-Friendly certified landscape professional to determine the amount and form or organic matter needed in your landscape.

If you have a soil question that you would like me to address in this series, please email me at sandrews@berkeley.edu. I will do my best to include a response for each question received.